Tetralogy of Fallot

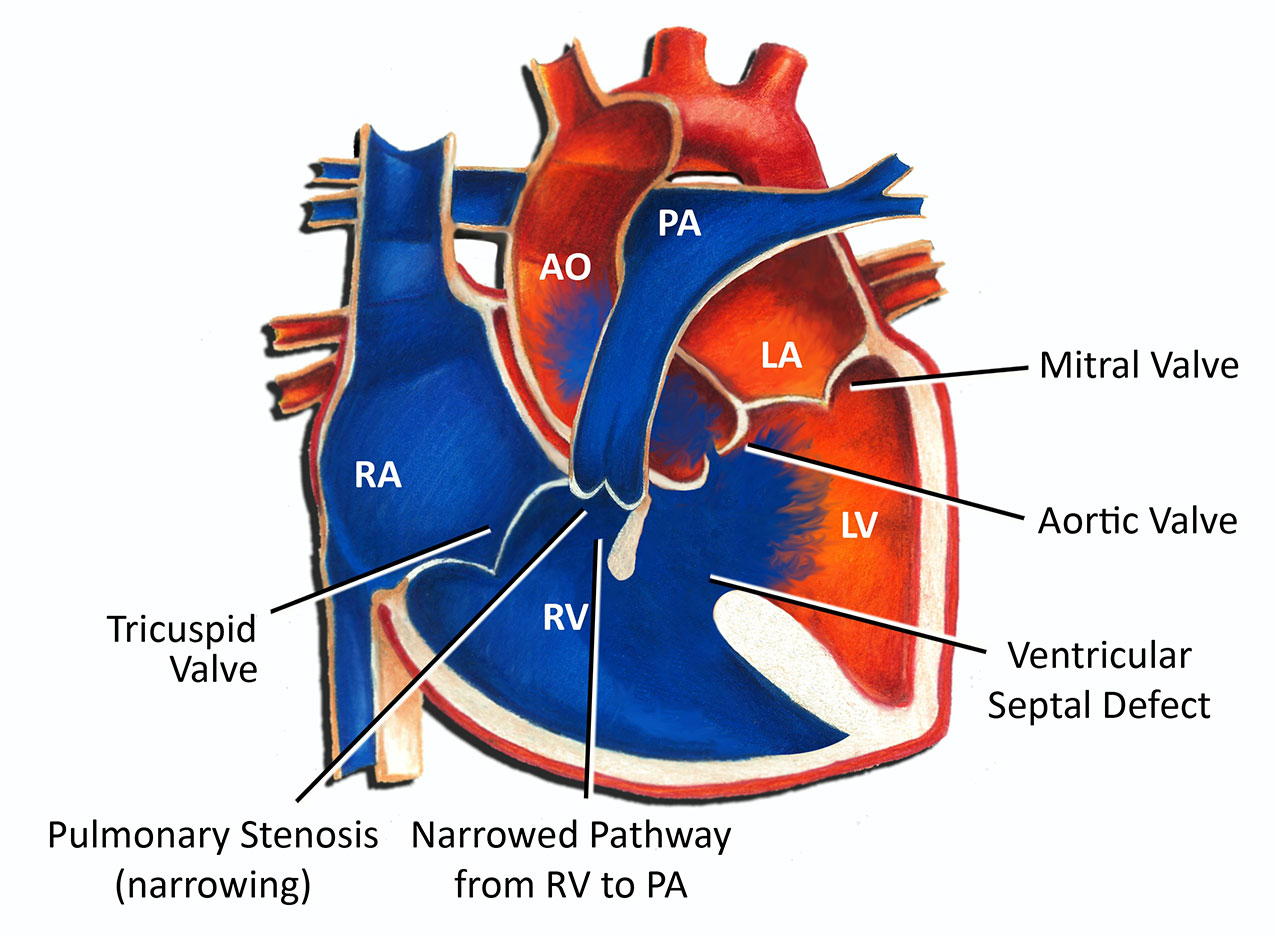

Tetralogy of Fallot is the most common cyanotic congenital heart defect. The overall incidence is about 5 in 10,000 individuals. Originally described in 1672, it was named after Dr. Étienne-Louis Arthur Fallot in 1888. Tetralogy of Fallot consists of 4 findings, a ventricular septal defect (hole in the lower wall of the heart), pulmonary stenosis (narrowing in the outflow of blood to the lungs), overriding aorta, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The first two findings, the VSD and pulmonary stenosis, are what determine the significance of tetralogy of Fallot.

The easiest way to think about tetralogy of Fallot is to visualize the lower wall of the heart, the ventricular septum, as 2 different pieces. Normally the upper piece fuses with the lower piece during development of the heart in the womb to form an intact wall. With tetralogy of Fallot, the upper wall gets out of alignment with the lower portion of the wall during development of the heart. It swings foward, towards the pulmonary valve, and thus creates obstruction or narrowing in blood flow out to the lungs.

Tetralogy of Fallot is a cyanotic heart defect. The term cyanosis means a bluish discoloration of the skin. The cause of cyanosis is a lower than normal blood oxygen level. Patients with tetralogy of Fallot are at risk for cyanosis because the narrowing of blood flow to the lungs in combination with a VSD or hole allows blood in many instances to bypass the lungs and go directly up to the body. The severity of cyanosis, and therefore the severity of symptoms, is determined by how the severity of pulmonary stenosis. Patients with more severe pulmonary stenosis are usually very cyanotic at birth and often need immediate attention. Patients with less significant pulmonary stenosis may have a normal or near-normal blood oxygen levels and may be seemingly fine at birth and for several months thereafter.

One of the risks of tetralogy of Fallot is what are called tet spells. A tet spell is an episode in which a child or infant becomes extremely blue and frequently agitated and out of breath. The spell is caused by a relatively sudden decrease in blood flow to the lungs. Tet spells can be precipitated by a number of things, including dehydration, agitation, or fever. Some children may have spells in the absence of any identifiable cause. Treatment of tet spells includes calming the patient, and administering oxygen or fluids if available. In many instances placing a patient in what is called the knee chest position will assist in terminating a spell.

Even in the absence of symptoms, tetralogy of Fallot ultimately causes significant problems in a number of ways. Long-standing cyanosis causes the body to produce more red blood cells. Over time this can clog the circulation and lead to several long-term negative consequences. In addition, the presence of a hole in the middle of the heart can predispose older patients to strokes and infections. Finally, the presence of long-standing pulmonary stenosis can cause thickening and ultimate failure of the right ventricle.

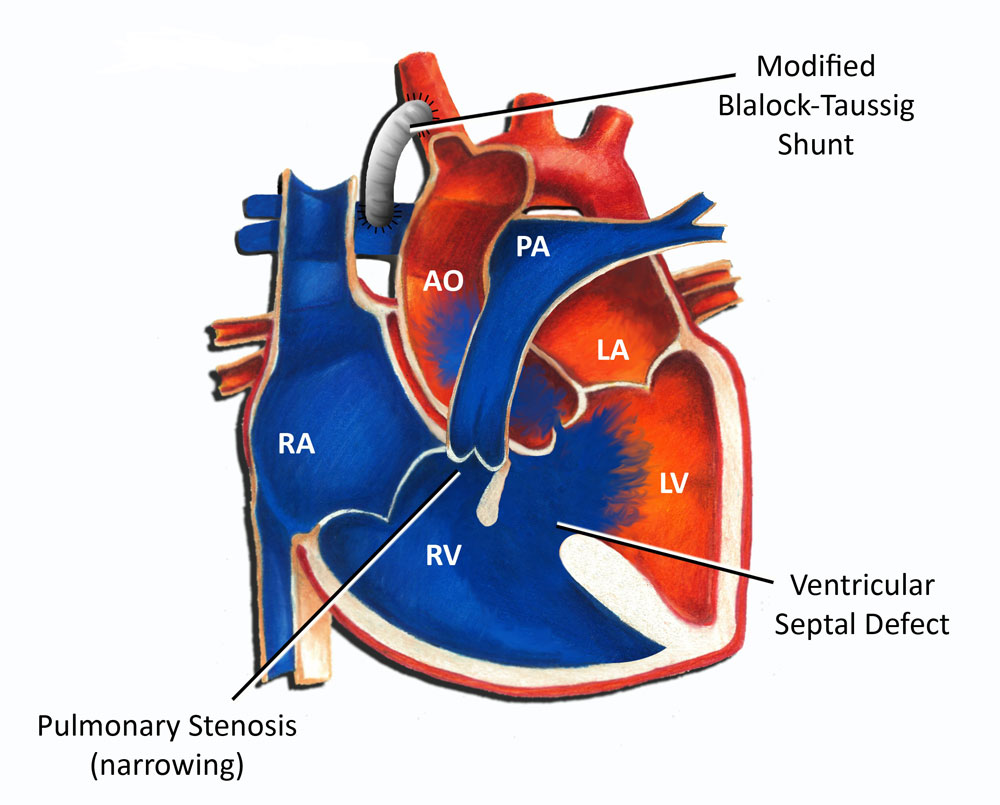

For these reasons, surgical correction of tetralogy of Fallot is always recommended. In the absence of any symptoms or significant cyanosis, surgical repair is usually performed sometime in the first year of life. Often allowing a patient to grow for several months can make the surgery technically easier and allow for a better outcome. In patients who are born with significant cyanosis, intervention is often needed early on, often in the first week of life. Usually this takes the form of a shunt. Originally performed by Drs. Blalock and Taussig in Baltimore in 1944, a shunt is simply a connection between the systemic circulation and the pulmonary circulation (see diagram below). A shunt allows for blood to gain access to the lung bed in order to obtain oxygen. Originally shunts were performed using patient's native vessels; in this day and age they are performed using artificial material.

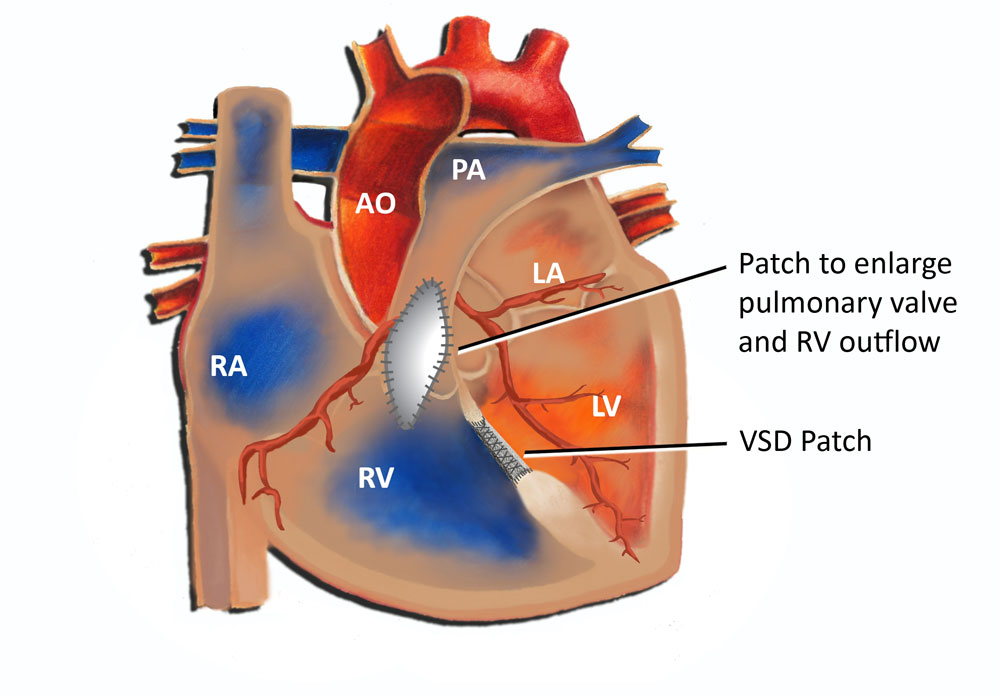

Complete surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot involves closing the VSD and widening the outflow to the lungs. This can take the form of removing muscle in the right ventricle beneath the pulmonary valve, incising and opening the pulmonary valve, and frequently cutting across the ring which the valve sits on, called the pulmonary valve annulus (see diagram below). Inevitably in most cases this leads to some degree of leakage of the pulmonary valve. The vast majority of patients following surgery for tetralogy of Fallot develop some degree pulmonary valve insufficiency or leakage. Although this does not cause an immediate problem, it can become an issue over time.

In the absence of significant complicating features, the vast majority of patients in this this day and age who undergo surgery for tetralogy of Fallot do very well. Most older infants require hospitalization between 4-7 days and usually have recovered nicely by the time they are discharged. The long-term prognosis of patients with tetralogy of Fallot is very good. A portion of patients with long-standing pulmonary valve regurgitation will ultimately require replacement of the pulmonary valve, usually as teenagers or young adults. Even with this, however, the majority do very well with normal development and little if any limitations.